The scene at Gate 23 of Shanghai Pudong International Airport on the morning of June 28, 2025, was one of controlled chaos. A young American tourist, let’s call her Sarah, was pulled from the security line, her brow furrowed in confusion. The security agent, polite but firm, pointed to the portable charger in her hand—a device she’d relied on for a week of navigating the city’s QR-code-driven landscape. With a flick of the wrist, the agent dropped her power bank into a large plastic bin already overflowing with hundreds of similar devices.1 No explanation was offered beyond a gesture towards a newly posted sign. Across the terminal, the scene was repeating itself, a quiet but widespread confiscation that left travelers bewildered and, in some cases, digitally stranded.

For an American audience, the importance of a power bank—or chōngdiànbǎo (充电宝) as it’s known here—might be hard to fully grasp. It’s not just a convenience for topping up your phone to scroll through Instagram. In China, a country that has largely leapfrogged the era of plastic credit cards, your smartphone is your wallet, your subway pass, your ID, and your ticket to virtually every part of modern life. A dead phone means you can’t pay for a taxi, order dinner, or scan the code to rent a shared bike. It’s a lifeline. This indispensability is reflected in the market’s staggering size: a 10 billion RMB (approximately $1.4 billion) industry in 2022, it was on a trajectory to explode to nearly 70 billion RMB by 2028.

This mass confiscation at airports across the country wasn’t just about a new, inconvenient rule. It was the dramatic climax of a product safety crisis that had been smoldering for weeks. It began with hushed warnings on college campuses, erupted into a massive, multi-brand recall affecting over 1.2 million devices 3, and ultimately forced a nationwide reckoning with the hidden vulnerabilities of China’s hyper-competitive supply chains and the true meaning of a government-mandated safety seal. This is the story of how a pocket-sized gadget, the symbol of China’s mobile-first modernity, suddenly became a symbol of its systemic risks.

The First Tremors: When the Power Drained from Top Brands

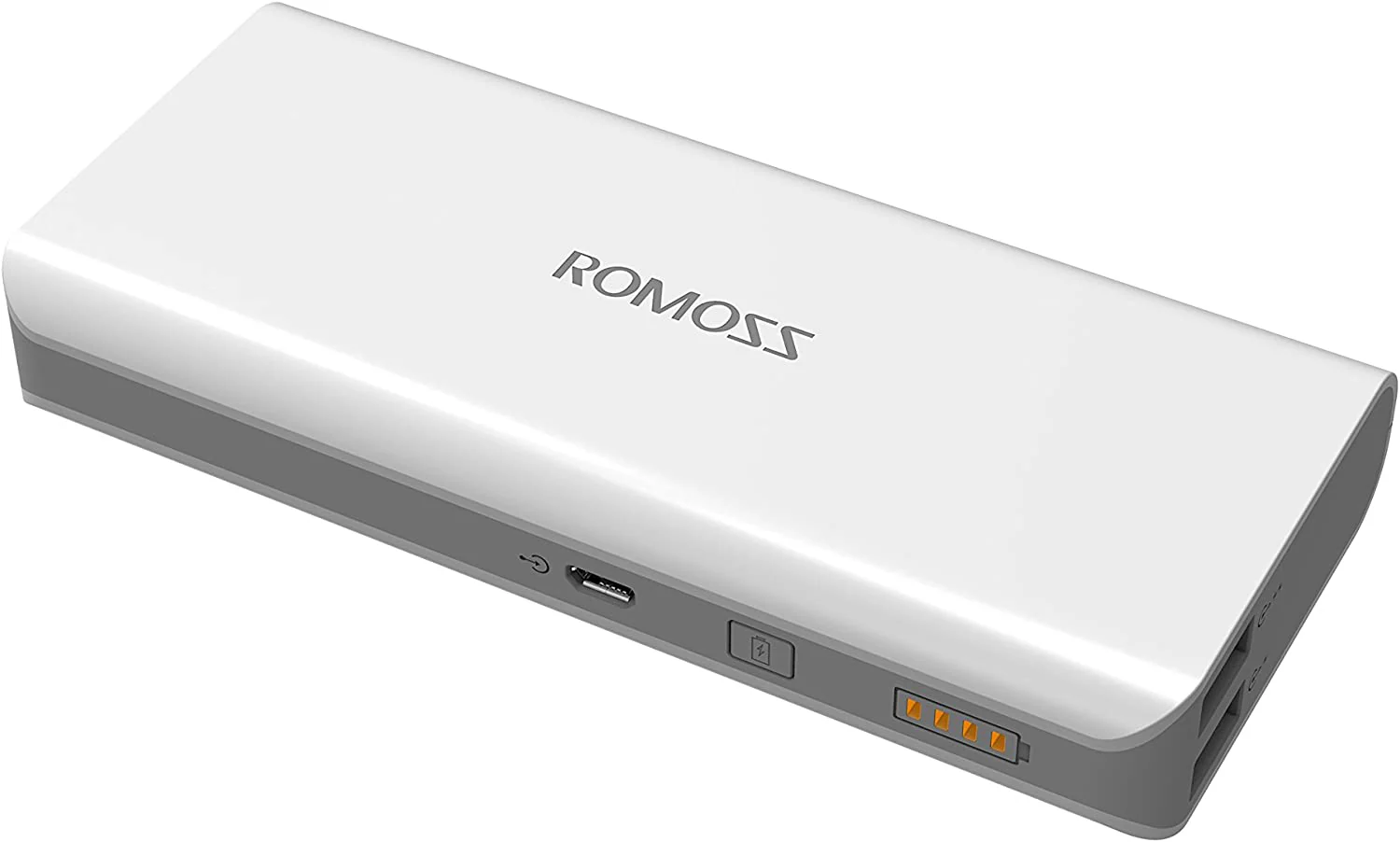

The Fall of a Titan: The Romoss Debacle

The crisis didn’t begin with a formal corporate announcement or a government decree. It started with a whisper network, a series of urgent warnings that bubbled up from the ground level. In early June 2025, students at several prominent Beijing universities began receiving official notices from campus security. The message was stark: stop using the 20,000mAh Romoss-brand power bank immediately. The reason cited was a disturbingly high risk of explosion during charging.

For Romoss, a company founded in 2012 and once hailed as an “online sales champion,” this was the beginning of a catastrophic collapse.4 The other shoe dropped on June 16, when the Shenzhen-based company, under pressure from the market regulator, made it official. It announced a recall of 491,745 power banks across three specific models (PAC20-272, PAC20-392, and PLT20A-152) manufactured over a year-long period between June 2023 and July 2024. The official reason given was vague but alarming: the products posed a risk of “combustion in extreme scenarios” due to an issue with raw materials in some battery cells.

What followed was a masterclass in how not to handle a crisis. Consumers who tried to follow the recall procedure were met with a wall of silence and dysfunction. The company’s official customer service hotline was reportedly disconnected, with a recorded message stating the number was “out of service due to non-payment” (欠费停机).5 Online, customers were either ignored by chatbot responses or, in some cases, found themselves muted or blocked from the company’s official e-commerce stores after posting complaints.5 One student recounted watching her roommate’s Romoss power bank explode in an elevator, filling the small space with a pungent, acrid smell and starting a small fire.5

The operational chaos fueled rampant speculation about the company’s solvency. By early July, media outlets reported that Romoss employees had been notified of a six-month halt to production and operations. Some R&D staff were allegedly reassigned to handle the flood of customer complaints before being put on indefinite leave.6 While the company issued a terse statement on social media denying it was going out of business, the damage was done.6 Its brand was in tatters, its products were being pulled from online shelves, and, most damningly, its numerous China Compulsory Certification (CCC) certificates for its power banks were suspended by the national regulator, rendering them unsellable.

A Different Approach: Anker’s Controlled Response

Just four days after the Romoss announcement, on June 20, another major player entered the fray. Anker Innovations, a globally recognized, publicly-traded company with a reputation for quality, issued its own recall. The contrast with Romoss could not have been more stark.

Anker’s recall was proactive and transparent. The company announced it was recalling seven of its basic power bank models, including the A1642, A1647, and A1257. Instead of vague warnings about “combustion,” Anker provided a specific technical explanation. It had discovered, during its own quality checks, that a particular supplier had made an “unauthorized raw material change” in a batch of battery cells. This change, they explained, could cause the “diaphragm insulation” inside the battery to fail after long-term use, creating a risk of overheating and fire. The company immediately terminated its contract with the supplier and halted sales of the affected models.

Crucially, Anker’s approach to its customers was exemplary. It offered three clear and generous compensation options: a full refund, a free upgrade to a newer, unaffected model, or a voucher for its online store equivalent to the original purchase price plus an additional 50 RMB bonus (about $7). This swift, clear, and consumer-centric response demonstrated a fundamentally different corporate ethos and went a long way toward preserving brand loyalty in the face of a serious product defect.

The Xiaomi Problem: Anxiety in the Absence of a Recall

The shockwaves from the Romoss and Anker recalls soon reached the 800-pound gorilla of the Chinese consumer electronics market: Xiaomi. The situation here was more ambiguous and, for consumers, perhaps even more frustrating. Xiaomi did not issue a formal recall. Instead, users discovered through online databases that the official CCC safety certification for one of its most popular models, the 20,000mAh PB2022ZM, had been quietly suspended by the authorities.7

This created a cloud of confusion and anxiety for millions of users. The case of a Guangzhou resident named Mr. Zhao, reported by Chinese media, perfectly captured the dilemma. He had purchased a power bank that, at the time, was fully certified and legally sold. Now, its certification was invalid, leaving him worried about its safety and its eligibility for air travel. When he contacted Xiaomi’s customer service, he was told that since the product had no quality issues at the time of sale and was not part of an official recall, the company would not offer a return or exchange. The advice he received was to simply “wait and see”.8

This non-response left millions of Xiaomi users in a state of limbo. They owned a product from a trusted brand that was not officially deemed “dangerous” enough for a recall but was now under a shadow of suspicion, its safety certification revoked, and its future at airport security checkpoints uncertain.7

| Brand | Recalled/Affected Models | Number of Units | Officially Stated Reason |

| Romoss | PAC20-272, PAC20-392, PLT20A-152 5 | 491,745 3 | “Combustion risk in extreme scenarios” due to “raw material issues.” |

| Anker | A1642, A1647, A1652, A1680, A1681, A1689, A1257 | Total recall (Romoss + Anker) > 1.2 million 3 | “Unauthorized raw material change in battery cells” leading to potential “diaphragm insulation failure.” |

| Xiaomi | PB2022ZM (Affected Status) 7 | Widespread (No recall issued) | CCC Certificate Suspended. Company stated no quality issues at time of sale. 8 |

The Heart of the Matter: A Single Supplier’s Critical Failure

The Common Denominator: Amprius (Wuxi) Co., Ltd.

As the crisis unfolded, journalists and industry analysts began connecting the dots. The recalls from Romoss and Anker, and the certification issues plaguing Xiaomi, all pointed to a single, critical point of failure in the supply chain. One name emerged as the common denominator: Amprius (Wuxi) Co., Ltd.. This company was the supplier of the faulty battery cells, and its client list read like a who’s who of the Chinese electronics industry, including not only Romoss and Anker but also other major brands like Xiaomi, UGREEN, and Baseus.8

The identity of the supplier was, in itself, a profound shock. This was not some anonymous, unregulated workshop churning out cheap components in a dusty corner of Guangdong. Amprius (Wuxi) was a high-profile, technologically advanced enterprise. It was established as a joint venture between its American parent company, Amprius Technologies—a prestigious Silicon Valley firm spun out of Stanford University—and the Wuxi Industry Development Group, a major Chinese state-owned enterprise.10 The company had been officially designated a “National High-Tech Enterprise” and had won multiple municipal and provincial awards for its “intelligent workshops” and technological innovation.10

The fact that a failure of this magnitude originated from a company with such a sterling pedigree was deeply unsettling. The initial, easy assumption—that this was a problem of low-end, corner-cutting factories—was proven wrong. The crisis pointed not to a lack of technological capability or prestige, but to a catastrophic failure of process, oversight, and ethics that could fester even within the walls of a supposedly world-class manufacturer. It shattered the simple narrative of “good” versus “bad” factories and hinted at a more insidious, systemic pressure at the heart of China’s manufacturing ecosystem.

The Technical Defect, Explained

To understand the danger, one must look inside the power bank. The device is essentially a simple plastic case wrapped around a battery. That battery cell constitutes up to 90% of the product’s internals and is the source of all the risk. The failure at Amprius stemmed from a critical defect within this core component.

While the companies’ statements were sometimes guarded, two primary technical explanations for the defect emerged from media reports and official statements.

- Unauthorized Material Change: Anker’s detailed disclosure pointed to an “unauthorized raw material change” affecting the diaphragm insulator. For the layperson, imagine the incredibly thin but crucial separator that physically keeps the positive and negative terminals inside a lithium-ion battery from touching. A short circuit is a battery’s worst nightmare. The allegation was that the supplier, without approval, swapped the specified, tested material for a cheaper, substandard one. Over time and with repeated charging cycles, this inferior material could degrade and tear, allowing the terminals to make contact and triggering a catastrophic failure.

- Metal Contamination: A later statement from China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) offered a slightly different, though related, explanation. It stated the recall was necessary because “metal foreign objects” were mixed into the battery cells during production.11 This is an even more direct path to disaster: microscopic shards of metal left over from the manufacturing process acting like tiny daggers inside the battery, eventually piercing the separator and causing the same devastating short circuit.

Regardless of the precise mechanism, the outcome is identical: a phenomenon known as thermal runaway. This is an uncontrollable, self-sustaining chain reaction where a short circuit generates immense heat, which in turn causes further chemical breakdowns that generate even more heat. The battery rapidly becomes an incendiary device, leading to violent venting of toxic gas, fire, and sometimes, explosion.

The Economic Driver: China’s “Involution” (内卷)

Why would a high-tech, award-winning supplier with a global reputation on the line commit such a fundamental error? Industry insiders and analysts pointed overwhelmingly to a single, powerful cultural and economic force: nèijuǎn (内卷), or “involution”.9 This piece of Chinese slang, which has entered the mainstream lexicon, describes a state of intense, zero-sum internal competition. It’s a race to the bottom where participants expend ever-increasing effort for diminishing returns, locked in a struggle not for progress, but for mere survival.

In the consumer electronics world, and particularly in the power bank industry, nèijuǎn manifests as a brutal, relentless price war.12 Brands are under constant pressure to offer higher capacity, faster charging, and more features, all while driving the retail price lower and lower. This decimates their profit margins, and that pressure is inevitably passed down the supply chain. Brands squeeze their component suppliers for lower costs, who in turn squeeze their own raw material providers. This creates a powerful, almost irresistible incentive for a supplier somewhere along that chain to cut a corner—to substitute a cheaper material, to skip a quality control step—to preserve a sliver of profit.9 Some reports even suggested that Amprius itself may have outsourced production of the faulty batches to a third-party factory that then made the unauthorized changes.

This crisis exposed a fundamental weakness in the very structure of the world-famous Shenzhen electronics ecosystem. The “Shenzhen model” is lauded globally for its incredible speed, flexibility, and vast network of hyper-specialized suppliers. This incident, however, revealed the dark side of that model. The reliance on a complex, multi-layered supply chain means that even a sophisticated brand like Anker may lack complete visibility and control over every component, especially those sourced two or three tiers down the line. A single point of failure at a critical node—in this case, the battery cell supplier—can trigger a catastrophic, industry-wide cascade.13 The culture of

nèijuǎn acts as a risk multiplier, prioritizing short-term cost reduction over long-term resilience and quality assurance. This wasn’t just the story of one bad supplier; it was a cautionary tale about the inherent fragility of a manufacturing ecosystem optimized for speed and cost above all else.

The Official Response: Flight Bans and the Mark of Compliance

The Hammer Comes Down: The CAAC’s New Rules

With evidence of a widespread safety defect and a rising number of in-flight incidents, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) acted with swift and sweeping force. Citing the urgent need to “ensure the safety of air transport,” the agency issued an emergency notice that would change the rules of travel overnight.14 Effective June 28, 2025, a new, much stricter regime for carrying power banks on domestic flights was implemented.

The new regulations were clear and uncompromising, built on three core pillars:

- The CCC Mark is Mandatory: All power banks carried onto a plane must bear a clear, complete, and legible “CCC” mark. Any device without the mark, or where the mark had been worn down and was unreadable, was now strictly forbidden.15

- Recalled Models are Banned: Any power bank whose brand, model number, or production batch matched those on an official recall list was prohibited from carriage.15

- Pre-existing Rules Reinforced: The CAAC took the opportunity to forcefully re-emphasize the long-standing international safety rules. Power banks must be in carry-on luggage only—never in checked baggage. They cannot be used to charge devices during the flight. And the strict capacity limits remain: devices with an energy rating under 100 Watt-hours (Wh) are permitted; those between 100Wh and 160Wh require airline approval and are limited to two per passenger; and any device exceeding 160Wh is banned entirely.

The Justification: A Clear and Present Danger

The CAAC’s sudden crackdown was not an overreaction. An expert from the China Academy of Civil Aviation Science and Technology revealed a chilling statistic: in the first half of 2025 alone, there had been 15 separate incidents of passenger-carried power banks catching fire or emitting smoke aboard commercial aircraft in China. This was nearly double the rate of the previous year.18 Incidents on flights from Hangzhou to Hong Kong and舟山 to 揭阳 had recently made headlines, with one event requiring passengers to pass bottles of water to crew members to help extinguish the flames.16

The unique danger of a lithium-ion battery fire at 35,000 feet cannot be overstated. The thermal runaway process is incredibly fast and violent, generating intense heat and large volumes of toxic, suffocating smoke. In the confined, sealed environment of a pressurized aircraft cabin, such an event is a life-threatening emergency that is notoriously difficult to contain.21 To illustrate the point, the fire department in Hangzhou conducted an experiment where they intentionally short-circuited a faulty power bank. It began billowing thick smoke in about 15 seconds, with its surface temperature rocketing to over 400°C (752°F)—far hotter than the ignition point of most cabin materials.16

Demystifying the “CCC”: China’s Seal of Approval (and its Discontents)

At the heart of the new flight regulations was a small, circular logo: the CCC, or China Compulsory Certification (中国强制性产品认证). Established in 2001, this mark is a mandatory safety and quality seal for a vast range of products sold or used in the Chinese market, from toys to home appliances to auto parts.23 For an American, it’s best understood as an analogue to the UL (Underwriters Laboratories) mark or Europe’s CE mark. To earn it, a product must undergo rigorous testing in a certified Chinese laboratory against national “GB Standards” and the manufacturing facility must pass an on-site audit.26

Here, however, lay the critical detail that fueled the chaos at airport security gates. The mandatory CCC requirement for lithium-ion batteries and power banks was a relatively new rule, having only gone into effect on August 1, 2024.28 This meant that millions of Chinese consumers owned perfectly legal and functional power banks that had been purchased before this date and therefore did not, and were not required to, have a CCC mark. In a Weibo exchange, Romoss itself acknowledged this, stating it was one of the first brands to get certified, implicitly confirming its older products lacked the mark.29 Overnight, these devices became contraband for air travel.

This situation exposed a deep and troubling paradox at the core of the regulatory system. The CAAC was now elevating the CCC mark as the definitive gatekeeper of flight safety. Yet, at the same time, industry insiders and media reports were deriding the certification process itself as a potential “compliance fig leaf” (合规遮羞布).30 The critique is that the system is vulnerable to gaming. A manufacturer, laser-focused on getting to market, can invest heavily in creating a “golden sample”—a perfect prototype—to pass the one-time certification tests, a process that can allegedly be aided by fraudulent submissions (虚假送检). Once the coveted certificate is obtained, however, the pressure of

nèijuǎn can lead to a relaxation of quality control on the mass-produced units that follow (认证后放松品控).30

The recalled products from Romoss and Anker were not from obscure brands that didn’t know how to pass a test; they were from established players who had successfully obtained CCC certification for their products. The failure was not one of design, but of production—a lapse in quality control that occurred after the certification was granted. This reveals the fundamental gap between certification and enforcement. The very system (CCC) being deployed as the solution to the safety crisis was being criticized for being part of the problem: a one-time check that offers no guarantee of ongoing, consistent quality. It’s a challenge that all regulatory bodies face, but one that is magnified in the unprecedented speed and scale of China’s manufacturing environment.

| Check | A Traveler’s Guide to China’s Power Bank Flight Regulations (Post-June 2025) |

| 1. The CCC Mark | Look for the ‘CCC’ logo on the device casing. Is it present, clear, and undamaged? If not, it is banned on domestic flights.15 |

| 2. The Recall List | Check if your brand and model number (e.g., specific Romoss/Anker models) are on an official recall list. If yes, the device is banned.15 |

| 3. The Capacity | Find the Watt-hour (Wh) rating. If it’s not listed, calculate it: Wh=V×Ah. (If capacity is in mAh, divide by 1000 to get Ah). Under 100Wh: OK to carry.100Wh – 160Wh: Requires airline approval.Over 160Wh: Strictly forbidden. |

| 4. The Bag | Your power bank must be in your carry-on luggage. It is NEVER allowed in checked baggage. |

| 5. In-Flight Use | You must not use the power bank to charge any device during the flight. If it has a power switch, it must remain off. |

A Traveler’s Advisory: Navigating the New Rules as a Foreign Tourist

So, what does all this mean for an American or other international visitor planning a trip to China? The answer depends entirely on your travel plans within the country.

For your international flight into China, the rules are generally more aligned with global standards. Airport authorities are primarily concerned with the universal safety regulations—the capacity limits (under 100Wh is fine, 100-160Wh needs airline approval) and ensuring your device isn’t on a recall list. They typically do not check for the domestic CCC mark on arrival.12 This means if you’re flying into Beijing, exploring the city, and then flying home from Beijing without any internal flights, your trusty power bank from back home—even without a CCC logo—is likely fine, as long as it’s not a recalled model.

However, the moment you plan to travel within China by air, the situation changes dramatically. The CAAC’s new regulations are strictly enforced for all domestic flights.22 If you plan to fly from Beijing to Xi’an to see the Terracotta Warriors, your power bank will be scrutinized at security. If it does not have a clear, legible CCC mark, it will be confiscated, no exceptions.12 The fact that it has a European CE mark or an American UL mark is irrelevant for domestic travel; passengers have reported having such devices confiscated because they lacked the specific CCC logo.12

Therefore, the key takeaway for any multi-city traveler in China is this: either purchase a new, CCC-certified power bank upon arrival or be prepared to have your foreign-bought one taken away at the airport. Given their ubiquity and low cost in any Chinese electronics market or convenience store, buying a local one is the safest and most hassle-free option. The distinction is crucial: international arrival is one thing, but domestic travel operates under a completely different and stricter set of rules.

After the Smoke Clears: Rebuilding Trust in “Made in China” Power

This was not simply a case of a few bad batches of a single product. It was a textbook example of systemic failure. A single point of weakness in the supply chain—the compromised battery cells from Amprius—was exploited by relentless economic pressures (nèijuǎn). This unleashed a latent safety risk that had been quietly escalating for years, evidenced by the rising number of in-flight fires. The crisis finally triggered a massive, top-down regulatory intervention from the CAAC, which, due to its necessary reliance on a flawed-but-essential certification system, inadvertently created its own secondary wave of chaos for millions of ordinary travelers.

The divergent paths taken by Romoss and Anker offer a crucial lesson in modern corporate responsibility. Romoss’s opaque, reactive, and dysfunctional handling of its recall decimated its brand reputation, perhaps irreparably. In contrast, Anker’s proactive, transparent, and consumer-focused strategy, while costly in the short term, likely preserved a significant amount of customer trust and loyalty. It was a clear demonstration that in today’s interconnected Chinese market, global standards of crisis communication are no longer optional.

The path forward requires a fundamental rethinking of safety and quality assurance. For brands, the crisis is a blaring wake-up call. They can no longer afford to simply trust a supplier’s paperwork or a one-time certification. The lesson is the urgent need for deeper, more intrusive supply chain auditing and continuous, independent quality control that verifies the integrity of components at every stage of production.

For regulators, the challenge is to evolve the CCC system from a simple gatekeeper to an active watchdog. The focus must shift from the one-time “golden sample” test to a robust system of unannounced factory inspections, random post-market product testing, and severe penalties for non-compliance. This is the only way to ensure the “compliance fig leaf” has real substance behind it. The government has signaled it understands this, with the market regulator launching a full investigation into Amprius, seizing its products, and promising to strengthen oversight of the entire industry chain.11

Ultimately, the great power bank recall of 2025 is more than a story about a faulty gadget. It is a messy, complex, and fascinating case study of the growing pains of a manufacturing superpower. It encapsulates the immense pressures of China’s hyper-competitive domestic market, the hidden fragility within its world-beating production engine, and the ongoing, often clumsy, struggle of its regulatory systems to keep pace with its own explosive economic and technological growth. It is a vivid snapshot of a nation grappling with the immense responsibilities that come with being the workshop of the world.

Works cited

- 罗马仕、安克充电宝召回直指电芯供货商,官方出手调查 – 北京日报, accessed July 7, 2025, https://xinwen.bjd.com.cn/content/s68620107e4b0bd64e2e046c4.html

- 喜良观经济|充电宝的事闹大了!-中国吉林网, accessed July 7, 2025, https://news.cnjiwang.com/jwyc/202506/3958465.html

- 民航局对携带“充电宝”登机发布明确规定 – 驻纽约总领事馆, accessed July 7, 2025, http://newyork.china-consulate.gov.cn/xw/201408/t20140809_4250970.htm

- FM9449航班旅客充电宝起火,航司官方回应来了 – 解放日报, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.jfdaily.com/news/detail?id=928757

- CCC产品认证 – 中国质量认证中心, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.cqc.com.cn/www/chinese/cprz/CCCcprz/

- 无3C标识不能登机充电宝安全新规的背后 – 中国科技网, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.stdaily.com/web/gdxw/2025-07/04/content_364904.html

- 新规今起施行!怎样判断你的充电宝能否带上飞机?注意几个关键词, accessed July 7, 2025, https://content-static.cctvnews.cctv.com/snow-book/index.html?item_id=10115919188225925497&toc_style_id=feeds_default

- 被召回充电宝问题指向电芯原料无3C认证未被召回的还能用吗? – 新华网, accessed July 7, 2025, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/20250630/8ab7e4ed20dd408db71229f316f19559/c.html

- 新规今起施行!怎样判断你的充电宝能否带上飞机?注意几个关键词 – 第一财经, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.yicai.com/news/102695793.html

- 充电宝风波不断小电池带来大警示 – 东方财富, accessed July 7, 2025, https://wap.eastmoney.com/a/202507063449199312.html

- 又一家充电宝品牌召回部分产品,快看你家有没有 – 新华报业网, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.xhby.net/content/s685743cee4b0f2411af6b612.html

- 无3C标识不能登机充电宝安全新规的背后 – 新华网, accessed July 7, 2025, http://www.news.cn/tech/20250704/f2f305296f7c49c7bb726afa99a40dfe/c.html

- 充电宝上飞机和高铁分别要满足哪些条件?看这几张图就明白了 – 第一财经, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.yicai.com/news/102700702.html

- 罗马仕、安克充电宝召回直指电芯供货商安普瑞斯无锡市场监管局正调查 – 东方财富, accessed July 7, 2025, https://wap.eastmoney.com/a/202506303443717838.html

- 罗马仕紧急召回超49万台充电宝!极端场景下可能产生燃烧风险 – 南方网, accessed July 7, 2025, https://news.southcn.com/node_179d29f1ce/271c70b6b5.shtml

- 又一家充电宝品牌召回部分产品 – 新湖南, accessed July 7, 2025, https://m.voc.com.cn/xhn/news/202506/29754032.html

- 罗马仕、安克充电宝召回直指电芯供货商安普瑞斯,无锡市场监管局正调查, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.yicai.com/news/102696799.html

- 充电宝新规引发热议,行业乱象曝光 – 解放日报, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.jfdaily.com/news/detail?id=939612

- 为何发布紧急通知?被拦下的充电宝如何处理?民航局回应 – 西部网, accessed July 7, 2025, http://m.cnwest.com/tianxia/a/2025/07/02/23147774.html

- 电报解读 – 财联社, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.cls.cn/detail/2077223

- 罗马仕风波,给充电宝行业敲响警钟| 新京报快评, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.bjnews.com.cn/detail/1751705569168067.html

- 民航局新规28日起实施:无3C认证或召回批次充电宝禁止登机多地机场已提前执行 – 中国之声, accessed July 7, 2025, https://china.cnr.cn/gdgg/20250627/t20250627_527231400.shtml

- 无3C标识不能登机充电宝安全新规的背后 – 东方财富, accessed July 7, 2025, https://finance.eastmoney.com/a/202507043447833848.html

- 中国共享充电宝行业研究报告, accessed July 7, 2025, https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202305251587158412_1.pdf?1685007875000.pdf

- 中國製行動電源災情擴大ANKER在中召回7型號、部分台灣有賣 – 中央社, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.cna.com.tw/news/acn/202506210174.aspx

- 电芯混入杂质存在自燃风险!两企业召回超120万台充电宝 – 新闻频道, accessed July 7, 2025, https://news.cnr.cn/native/gd/20250706/t20250706_527248078.shtml

- 49万台充电宝召回,罗马仕风波持续!业内人士:低价电芯为“元凶” | 网事, accessed July 7, 2025, https://m.dutenews.com/n/article/8900557

- 还原充电宝召回风暴:缺陷电芯如何避开监管流入市场? – 证券时报, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.stcn.com/article/detail/2271189.html

- 小米一款充电宝3C认证暂停,用户担心乘机受阻,多机场回应 – 华龙网, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.cqnews.net/1/detail/1390064100974227456/web/content_1390064100974227456.html

- 无3C标识不能登机充电宝安全新规的背后, accessed July 7, 2025, http://www.tynews.com.cn/system/2025/07/04/030903705.shtml

- 专家:今年已发生15起充电宝在飞机上起火冒烟事件 – 北京日报, accessed July 7, 2025, https://xinwen.bjd.com.cn/content/s68614e90e4b0aabe0a02f9e3.html

- 安普瑞斯(无锡)有限公司 – 浙江大学就业服务平台, accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.career.zju.edu.cn/jyxt/sczp/zpztgl/ckZpgwList.zf?dwxxid=JG1223583

评论