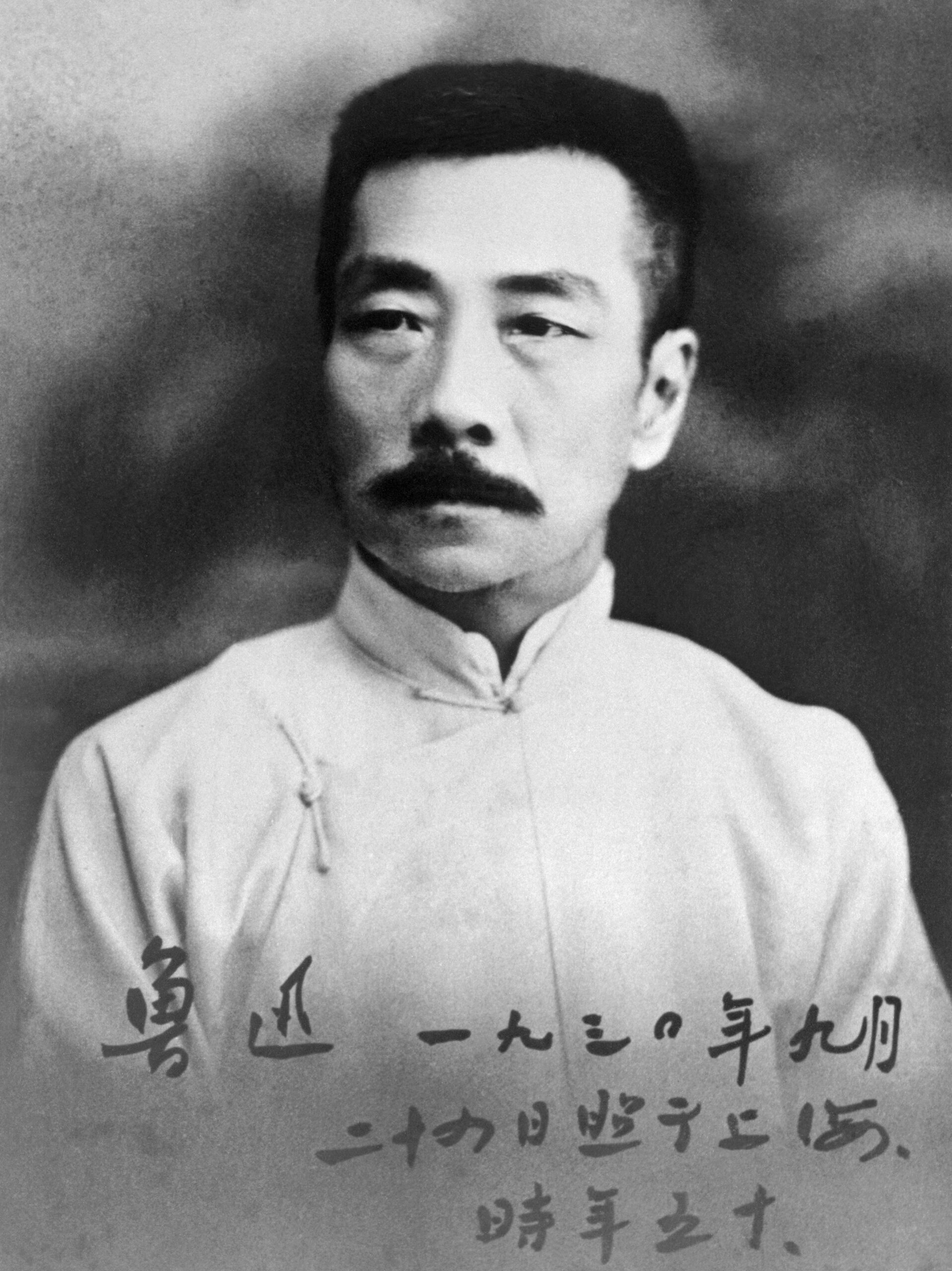

Lu Xun is hailed as one of the greatest literary figures in China and a prominent revolutionary during the nation’s modern history. To some extent, he’s dubbed the “Father of Modern Chinese Language.” Before his time, the majority of Chinese writings employed Classical Chinese, a style distinct from everyday spoken language. Both domestically and internationally, many of Lu Xun’s writings are well-recognized and acclaimed.

While most people become acquainted with him through his works, very few details of Lu Xun’s personal life make it into his official publications. Given his contrasting political views with the Republic of China government back then, disclosing personal aspects of his life might have posed a risk to his safety. His writings reflect an aspiration towards socialism, even though he never formally joined the Chinese Communist Party.

Lu Xun’s literary contributions are widespread and well-documented, but the minutiae of his daily life remain largely under the radar. What were his favorite foods? How did he prefer to dress? Which brand of cigarettes did he favor?

Today, I stumbled upon an article titled Lu Xun’s Modest Lifestyle on the Chinese internet. This piece meticulously delves into various aspects of this iconic writer’s life from a century ago – from his sartorial choices to his culinary preferences. Through this article, I not only gained insights into Lu Xun’s way of life but also glimpsed the lifestyle of a relatively affluent celebrity in China a hundred years ago.

I’ve noticed a scarcity of such information in the English-speaking digital realm. Hence, I’ve taken the liberty of translating the article into English for a broader audience’s appreciation.

Part 1

Throughout the Republic of China era, among well-known cultural figures, Lu Xun’s material life was neither impoverished nor as affluent as widely rumored. What troubled Lu Xun more was not household expenses but the larger concerns of the nation. Xu Guangping remarked that those deeply engrossed in their ideal lives often hold contrasting views about material concerns.

Xu Guangping, once a student under Lu Xun, quickly sketched him clad in patched clothes with upright hair. He wasn’t particular about his attire. As a child, family members would caution him when wearing new clothes for fear of him staining them, constantly monitoring and warning him, making him feel restricted.

While studying in Nanjing, Lu Xun didn’t have spare money for clothing. His cotton robe was tattered and threadbare, with no padding left at the shoulders. When he first arrived in Shanghai, his many-years-worn blue cotton robe tore. Xu Guangping had a new one made for him in blue wool, but he found it too slippery and uncomfortable, refusing to wear it.

Only in the final year of his life, as his frail body couldn’t bear heavy clothing, did he have a brown silk-padded robe made. He was wearing it when he passed away. It was arguably the most refined piece of clothing he had worn since adulthood.

With his simple attire, unkempt and defiant hairstyle, it was clear he rarely groomed. He often wore cloth shoes and seldom leather ones. Such an appearance, amidst the fashion-conscious streets of Shanghai, embodied his own description: a worn hat concealing one’s face while walking through a bustling market.

Part 2

Once, Lu Xun, without any effort at grooming, went to visit a British friend who was staying in Shanghai’s most luxurious hotel of that time, located on the city’s main street (now Nanjing Road) on the seventh floor. As he took the elevator, the elevator operator looked him up and down and evicted him from the lift. Lu Xun had no choice but to climb the staircase to the seventh floor.

Two hours later, as the British friend escorted him to the elevator, the embarrassed operator couldn’t face him. Lu Xun brushed it off with a chuckle.

In Mr. Xia Yan’s memory, Lu Xun would always be seen in an inexpensive Western-style sheer gown (also known as a gauze robe) from Dragon Boat Festival till Double Ninth Festival – almost half a year. In the fifteenth year of the Republic of China, when he traveled from Beijing to Xiamen to teach and made a stop in Shanghai, friends held a banquet in his honor. He was still dressed in that same Western-style sheer gown.

Yao Ke’s first impression of Mr. Lu Xun was of a man dressed carelessly in an old, deep-blue gabardine robe, with wide cuffs that revealed a dark green flannel shirt underneath, and feet clad in black canvas shoes with rubber soles. Yet, it was his eyes that stood out – they seemed not only well-read but also having witnessed the entirety of the human experience. As Yao Ke recalled, “One can’t help but feel his immense presence and one’s own insignificance.”

While Lu Xun might not have paid much attention to what others wore, as he once mentioned, “I don’t really notice what others wear,” when asked for his aesthetic opinion, he’d voice it. For instance, when writer Xiao Hong wore a fiery red top and sought his opinion on whether it looked good, he candidly remarked it wasn’t very attractive. The reason? The red top paired with a coffee-colored plaid skirt resulted in a “muddled combination.”

Lu Xun actually had a good aesthetic sense when it came to clothing, and his advice still holds true today. “People who are plump should wear vertical stripes; vertical lines elongate the figure, while horizontal ones widen it,” and “Thin individuals shouldn’t wear black, and plump individuals shouldn’t wear white,” and so on. Interestingly, during his early years studying in Japan, he was quite fashionable and continued wearing long robes upon returning to China. From the time of his painful celibate marriage to Zhu An in 1906, till he began living with Xu Guangping in 1927, spanning a stifling 21 years, one wonders if this period played a significant role in shaping Lu Xun’s unkempt appearance?

Part 3

In the Chinese literature textbooks of middle schools, references to gourmet dishes in Lu Xun’s works are quite scarce.

I initially thought Lu Xun had a fondness for beans, like the monk beans in “A Comedy of Ducks”, the dried green beans Run Tu brought for him in another story, and the anise beans from the Xian Heng Tavern. However, I soon realized that this was a misconception.

Contrary to his modest dressing habits, Lu Xun was much more passionate about food, often organizing and participating in dining events. Through a twist of fate, I’ve known Mr. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s eldest grandson, for 16 years. In 2008 and 2009, I was honored to be invited to birthday celebrations for Zhou Haiying, Lu Xun’s only child, held in a hotel near Hongkou Lu Xun Park and the Shanghai CPPCC Hall. After that, most of our gatherings took place at Kong Yiji Tavern.

Curious about what Lu Xun loved to eat, Lingfei suggested I delve into Lu Xun’s diaries.

From 1912 to 1926, Lu Xun lived and worked in Beijing, first for the Ministry of Education and later part-time at a university. Post-1918, his position at the Ministry was akin to that of a department head today, making him a mid-level official during the rule of the Beiyang warlords. Despite the modest title, he wielded considerable influence. Being a renowned scholar and writer, he had extensive connections and an active social life.

In February 1916, Lu Xun noted in his diary, “This month, my salary has been raised to the third grade, increasing from 280 to 300 silver dollars.” Back then, the average monthly living expense in Beijing was about 3 silver dollars.

In just the year 1913, Lu Xun dined out 294 times, visiting 65 different restaurants, with Guangheju being the most frequented. He was also fond of Taifenglou, known for dishes like stir-fried tripe, stir-fried eel, deep-fried assorted bites, and steamed duck. Hejixiaoguan, near the Ministry of Education, was renowned for its beef and mutton. Lu Xun had a penchant for their beef noodle soup, which was both delicious and affordable.

During his time in Shanghai, Lu Xun’s favorite dining spot for gatherings was Zhiweiguan, known for its Hangzhou cuisine. Beggar’s Chicken, Dragon Well shrimp, Dongpo pork, and Monochoria korsakowii soup were among his favorites.

Zhejiang native Yu Dafu was one of Lu Xun’s most frequent dining companions. They often visited places like Wumalu Sichuan Restaurant and Taolechun. Spicy fish with mung bean noodles, pot tofu, stir-fried kidney slices, and Shaoxing wine were their regular orders. It was at one such dining table that Yu Dafu learned of Lu Xun’s passing.

Lu Xun had a strong palate, favoring spicy foods. He believed that spicy foods induced sweating and alleviated fatigue. This preference may have originated during his student days in Nanjing, where he couldn’t afford thick winter clothes in the cold weather and turned to chili peppers to keep warm.

Part 4

Within the Lu Xun Memorial Museum, there are two cookbooks from Lu Xun’s household, detailing the daily menu when he first settled in Shanghai. During this period, he and Xu Guangping had both their lunch and dinner prepared and delivered by renowned Shanghai restaurants. Their meals, usually consisting of two meat dishes and one vegetable dish, rarely repeated within a week. The dishes predominantly featured Cantonese and Shaoxing cuisines, with a touch of Shanghai flavors.

As Xu Guangping recalls, Lu Xun wasn’t fussy about his food, but he always preferred fresh dishes of the day. He wasn’t fond of leftovers, with the exception of cured ham, which he could enjoy over several meals. After moving to Shanghai, Lu Xun also took to drinking more tea. In Beijing, he had a unique old-fashioned teacup with a lid. In Shanghai, he transitioned to brewing tea in a small pot.

Later on, writers like Xiao Hong and Xiao Jun often came over to dine at Lu Xun’s place. Xu Guangping would always cook generous portions. During his time in Shanghai, Lu Xun would wear V-neck wool vests knitted by Xu Guangping, relishing the home-cooked meals she prepared. Those nine years, the last of his life, were some of his most heartwarming.

Lu Xun often wrote late into the night, with a regular stash of nuts like walnuts and peanuts, as well as pastries and cakes. He had a sweet tooth. During his study years in Japan, he was particularly fond of yokan: a dessert made from red beans and chestnut flour.

In Beijing, Lu Xun frequently indulged in French-style cream cakes and the Manchu dessert ‘saqima’. He would also frequent Daoxiangcun, a high-end bakery in the capital, to buy pastries and side dishes. It’s often said that men with a penchant for snacks and desserts have a hidden streak of romance and purity.

Lu Xun and his younger brother, Zhou Zuoren, had contrasting tastes. Zhou never thought much of Beijing’s pastries, once writing, “I wandered Beijing for ten years and never found a good pastry.”

After settling in Shanghai, if Xu Guangping could prepare him something to eat around midnight—like a Shaoxing-style fried rice with green onions, with both the eggs and rice fried till slightly crispy, accompanied by half a glass of wine—he would be utterly content.

Having traveled extensively across China and Japan, Lu Xun respected and appreciated most regional cuisines and integrated himself within those culinary cultures. However, he found Fujian cuisine to be rather unpalatable, particularly disliking their use of red fermented rice. This might have been influenced by his somewhat somber mood during his teaching years at Xiamen University.

For Lu Xun, who had a taste for strong flavors like salted, spicy, and fermented foods, the light and fresh Fujian cuisine might have felt rather bland. During his time in Xiamen, he consumed a golden cinnabar pill daily and also took wheat germ cod liver oil. As for fruits, in his “Letters from Two Cities,” Lu Xun wrote to Xu Guangping, “Fu Yuan brought back starfruit. I tasted it last night. While not particularly delicious, it was juicy. Its aroma, however, surpassed many other fruits.”

Back then, Lu Xun’s salary from Xiamen University was 400 silver dollars a month.

Part 5

Lu Xun had a fondness for smoking. On regular days, he preferred affordable roll-up cigarettes: brands like “Gold Label,” “Brand Sea,” and “Robber.” He would consume about fifty of these a day. “Black Cat” was his top choice, but it was pricier, and he indulged in it only occasionally. Every night, Lu Xun would make it a point to have his “Robber” cigarettes along with a particular snack he enjoyed.

He kept two types of cigarettes on hand. The pricier ones, called “Front Gate,” were reserved for guests, while the cheaper variety, which cost about four to five cents for fifty sticks, was for his personal use.

As for alcohol, Lu Xun wasn’t a heavy drinker, but he always enjoyed a little now and then. In Beijing, he drank the local spirit, turning to it particularly during times of great joy or frustration. Upon moving to Shanghai, he shifted mainly to rice wine, but he also occasionally indulged in other drinks like “Five Plus Leather,” “White Rose,” beer, and brandy.

Coffee shops hold a unique place in the history of the Communist Party of China. These establishments, primarily located in concession areas, were frequented by the societal elite. Underground communist operatives often used them as discreet venues to exchange information, providing vital cover for revolutionary activities. In Lu Xun’s diary, there are frequent entries like “In the afternoon, went to the café with Rou Shi” or “In the afternoon, went with Maeda Tora and Nishiyama to the Osterreich Café.”

Back in the day, the café in Hongkou district was a frequent secret rendezvous point for Lu Xun and members of the Leftist Association, as well as representatives of the underground communist movement. In fact, the preparatory meeting for the first Leftist Association in 1929 was held here.

There’s a famous quote by Lu Xun: “Where is there a genius? I’ve spent the time others use for coffee breaks on my work.” Yet, he did enjoy his coffee, often using cafes as meeting spots for discussions with friends and colleagues. Wang Yingxia once recalled an evening after dinner with Lu Xun, Xu Guangping, and Yu Dafu. As a server brought coffee for everyone, Lu Xun turned to Xu Guangping and remarked, “Miss Xu, with your sensitive stomach, it’s best you skip the coffee. Perhaps have some fresh fruit instead.”

Part 6

Lu Xun once owned two properties in Beijing. The first was located in Badaowan: a traditional courtyard house with three sections, totaling 32 rooms. He paid a hefty sum of 3,500 silver dollars for it. To give some context, Lu Xun’s monthly salary from the Ministry of Education was 350 silver dollars at the time, not including earnings from his writings and part-time lectures at eight institutions. To compare, a regular laborer’s monthly salary was 3 silver dollars, an elementary school teacher earned 10 silver dollars, a regular doctor made 40, and a housemaid earned 2.

The second property was situated on West Third Street. This residence was mentioned in Lu Xun’s work where he described, “In my backyard, there are two trees. One is a date tree, and so is the other.” It’s the current Lu Xun Museum. Back then, he purchased this property for 800 silver dollars. However, it was in a dilapidated state and required extensive renovations. Including deed taxes and other costs, he spent a total of 2,100 silver dollars.

Both properties drained Lu Xun’s savings, leading him to take on debts which took years to repay. After purchasing these homes, Lu Xun’s financial situation was never particularly comfortable again.

In Shanghai, Lu Xun never owned a property. He rented three different residences, all in the Hongkou district. Initially, he stayed at Jingyun Lane, followed by the Ramos Apartment, and finally at the Mainland New Village.

Shanghai was a significant stage for China’s revolutionary liberation movement. In the 1920s and 1930s, many intellectuals and altruistic figures gathered here. It was also a crucial chapter in Lu Xun’s life, encompassing his personal experiences, cultural engagements, and battles.

The presence of Lu Xun in Shanghai during the 1930s added an irreplaceable cultural weight to the city. His first residence in Shanghai was No. 23, Jingyun Lane, Yokohama Road. The deposit for the house was 50 silver dollars. In the autumn of 1927, just five days after arriving in Shanghai, Lu Xun and Xu Guangping moved in from the Republican Hotel.

Jingyun Lane consisted of typical Shikumen (stone gate) houses built around 1925 with brick-wood structures. Lu Xun’s home was around 70 square meters, a three-story south-facing building. He lived on the second floor, while Xu Guangping resided on the third. They spent a little over two years there, occupying both No. 23 and later No. 17, and briefly shared the residence with Zhou Jianren’s family at No. 18.

Soon after moving to No. 17 Jingyun Lane, Xu Guangping gave birth to their only child, Zhou Haixing, at the Japanese Fukumin Hospital on North Sichuan Road, later known as Shanghai’s Fourth People’s Hospital.

Not only did Lu Xun reside in Jingyun Lane, but other prominent cultural figures like Ye Shengtao, Feng Xuefeng, Mao Dun, and others did as well. After moving to No. 17, Lu Xun handed over No. 23 to Rou Shi and his companions. Here, Rou Shi wrote the acclaimed “February” and was later arrested and executed.

“In sorrow, I see friends turn to ghosts, in anger, I seek verses amidst daggers,” are lines Lu Xun penned in “For the Forgotten Memory,” reminiscing about Rou Shi.

Part 7

Lu Xun frequently visited the Neishan Bookstore located on North Sichuan Road. On his first visit, he bought four books, spending a total of 10.2 yuan. From then on, he became a regular customer, buying books, meeting guests, and attending salons. He even took refuge in the bookstore’s mezzanine during difficult times. The store owner, Neishan Wanzao, became a dear friend of Lu Xun’s family.

Today, the first floor of the former Neishan Bookstore site is occupied by the Industrial and Commercial Bank, while the second floor serves as a display hall for the bookstore and is open to the public. In 2021, marking the 140th anniversary of Lu Xun’s birth, the “1927 Lu Xun & Neishan Commemorative Bookstore” project was initiated. The building underwent renovations to upgrade its function, aiming to establish a new cultural landmark in the area. To this day, the bookstore has evolved into a prominent hub for cultural exchange in Shanghai, reintegrating its rich heritage into the urban fabric.

On the eighth day of the Lunar New Year this year, I had my first cup of coffee after the holiday at the “1927 Lu Xun & Neishan Commemorative Bookstore.” I purchased a book titled “Letters and Notes of Lu Xun” and enjoyed a Japanese-style coffee called “Morning Flower, Evening Collection.” This latte, sprinkled with dried jasmine and gardenia, gave me a moment of tranquility during the festive season. Feeling quite content, I posted on my social feed: “As the new year unfolds, many moments start to feel deeply personal.”

In May 1930, Lu Xun moved to the Ramos Apartment on North Sichuan Road (now Beichuan Apartments), which was close to the Japanese Army Command Center at that time. The rent was 500 yuan, with an initial payment of 200. This Western-style international apartment complex was financed by a British man named Ramos. Lu Xun’s family was the only Chinese household there, and they rented it through Neishan Wanzao. In March 2021, it was listed among the first batch of Shanghai’s Revolutionary Cultural Relics.

The unit Lu Xun lived in was a two-room suite. Its layout was not ideal, with only the largest room, which was used as Lu Xun’s bedroom and study, having windows. Prominent figures like Roushi, Feng Xuefeng, Yu Dafu, and Neishan Wanzao were frequent visitors.

Red Army General Chen Geng also secretly met with Lu Xun here. Chinese Communist leader Qu Qiubai sought refuge here for extended periods in 1932 and 1933. During this period, Qu Qiubai’s pseudonym frequently appeared in Lu Xun’s works and diaries. Later, with Lu Xun’s help, Qu rented a small pavilion room nearby at 12 Dongzhao Lane.

Both Jingyun Lane and the former Ramos Apartment where Lu Xun lived are now residential and are not open to the public.

The famous No. 9 Dalu Village was Lu Xun’s last residence in Shanghai and where he felt most at peace. Located at 132 Shan Yin Road, No. 9, it is a protected cultural heritage site in Shanghai.

Today, No. 9 Dalu Village retains its original appearance from Lu Xun’s time. Entering, there’s a small courtyard with a garden. The front room on the ground floor serves as the living room, equipped with a bookcase and a desk gifted by Qu Qiubai. The dining room at the back has a Western-style coat rack. On the second floor, Lu Xun’s bedroom doubles as a study. It’s furnished with an iron bed, wardrobe, dressing table, and prints. Absent is a sofa, but there’s a wooden armchair in front of the writing desk. When he needed a break, he’d rest on the old rattan lounge chair next to the desk and read a newspaper.

The clock on the dressing table is forever frozen at 5:25 a.m., and the calendar remains unchanged, showing October 19, 1936, the moment when this literary giant passed away. The front room on the third floor has a balcony and was the bedroom of Zhou Haiying and the nanny. The back room served as a guest room, providing shelter to individuals like Qu Qiubai and Feng Xuefeng.

Part 8

Lu Xun, the esteemed Chinese writer, was known for his simple living. His bed was a hard wooden plank with thin bedding, a testament to his asceticism. This leads us to another aspect of his life, his platonic marriage with Zhu An. One of Lu Xun’s close friends, Yu Dafu, revealed that during his prime, Lu Xun wore single-layer trousers and slept on a hard bed to suppress his desires.

After moving to Shanghai, Lu Xun switched to a common iron bed.

Several times a year, I find myself drawn to visit house number 9 in Dalu Village. This modest residence exudes a unique ambiance, as if one can still sense the warmth, intelligence, and hearty laughter of the great man. It brings to mind the saying: “Death is not the loss of life, but stepping out of time.”

Lu Xun’s lifelong dedication to examining, exposing, criticizing, and rectifying the flaws of national character is one of the reasons he remains so revered.

Xu Shoushang remarked, “Some believe Lu Xun was worldly-wise, while others feel he was naive. In truth, he simply didn’t conform to the times.” Neiyama Kanazawa described Lu Xun as a small man with a grand aura, not living and working through physical strength but sustained by his spirit.

One of the few luxuries Lu Xun allowed himself was taking a car to watch movies. Due to the political climate, when he went out with Xu Guangping, they mostly walked. For longer distances, they took a car, seldom a tram, and never a rickshaw, citing the inconvenience of avoiding unexpected situations.

Whenever he watched a movie, he always bought a first-class ticket, never noting down the expense. Records indicate that Lu Xun watched 171 movies in total, with 141 of them during his time in Shanghai. Even shortly before his death on October 19th, 1936, he had watched movies on October 4th, 6th, and 10th.

Some who peruse Lu Xun’s diaries note his frequent movie outings and feel disappointed, expecting his life to have been more austere. Xu Guangping defended him, stating, “He faced hardship his whole life, from hunger to poverty, to the point his hair turned white from stress. Taking a break to rejuvenate and then compensating with doubled work efforts… is that really so excessive?”

Throughout his life, Lu Xun maintained the lifestyle of a student and a soldier, embodying the traditional Chinese virtue of self-discipline. Xu Guangping felt that “he was thoroughly ‘rural’ in every aspect.” Although the last ten years of his life were made more comfortable under her care, she recalled, “I can’t remember anyone saying that Lu Xun’s life prioritized spirit over material… He’d start work as soon as he woke up, often not eating until dinner, which would be just two or three dishes, accompanied by half a cup of light wine.”

评论